The death of a person undergoing medical treatment is cause for serious reflection on the part of caregivers. Historically, procedures have been developed to help understand the circumstances of such deaths. These procedures range from a focus on the person (e.g., such as a medical status review and/or psychological autopsy of the deceased patient) to a broader focus on the caregiving environment and caregiving procedures (e.g., mortality review committees). Such procedures have become routine within hospitals and other health care organizations and have expanded to encompass a broad spectrum of agencies, including organizations addressing issues of child welfare and family violence. The expectations of such reviews have been extended to accredited addiction treatment organizations, but such reviews in my experience have focused primarily on patients.deaths that occur during detoxification or during inpatient or residential treatment. More common and less addressed is the death of a patient in the days, weeks, or months after primary inpatient or outpatient treatment has been completed.

The death of a person undergoing medical treatment is cause for serious reflection on the part of caregivers. Historically, procedures have been developed to help understand the circumstances of such deaths. These procedures range from a focus on the person (e.g., such as a medical status review and/or psychological autopsy of the deceased patient) to a broader focus on the caregiving environment and caregiving procedures (e.g., mortality review committees). Such procedures have become routine within hospitals and other health care organizations and have expanded to encompass a broad spectrum of agencies, including organizations addressing issues of child welfare and family violence. The expectations of such reviews have been extended to accredited addiction treatment organizations, but such reviews in my experience have focused primarily on patients.deaths that occur during detoxification or during inpatient or residential treatment. More common and less addressed is the death of a patient in the days, weeks, or months after primary inpatient or outpatient treatment has been completed.

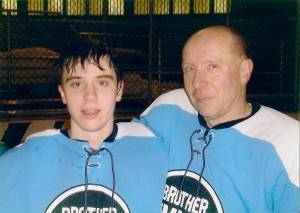

Families who have lost a family member to addiction following one or more episodes of addiction treatment are beginning to move beyond their own grief and guilt to ask questions about the quality of addiction treatment their family member received and how treatment assumptions and procedure could be improved to prevent such tragedies for other families. Bill Williams is one such family member who is turning his grief into advocacy. The post below is one worthy of serious reflection by addiction professionals and treatment administrators. It suggests two obvious first steps: 1) every person entering addiction treatment (regardless of subsequent discharge status) should receive assertive recovery check-ups for at least one year (and preferably for five years), and 2) the death of any patient within one year of discharge following addiction treatment should be rigorously reviewed with a focus on identifying any changes in service practices that could potentially prevent such deaths.

March 26, 2015 Post by Bill Williams (posted with permission)

Discussions about Substance Use Disorder in its various guises often include ideas about "Rock Bottom." The notion being that sooner or later the afflicted have to experience a life altering event--overdose, incarceration, getting kicked out of school, losing a job, getting kicked out of home, to name a few, that shocks them into lasting change. Our family, too, heard this advice from multiple sources while our son, William, struggled with his use of heroin and we struggled to cope and understand.

Discussions about Substance Use Disorder in its various guises often include ideas about "Rock Bottom." The notion being that sooner or later the afflicted have to experience a life altering event--overdose, incarceration, getting kicked out of school, losing a job, getting kicked out of home, to name a few, that shocks them into lasting change. Our family, too, heard this advice from multiple sources while our son, William, struggled with his use of heroin and we struggled to cope and understand.

The problem is this. The rocks at the bottom are strewn with dead bodies, including that of my son. Death is rock bottom. Anything else is just a serendipitous, albeit uncomfortable, landing on an outcropping on the way down. It may be a tough climb back. There may be other falls. But it's not death.

I have recently come up with the idea of writing a letter to everyone who helped treat William along the tortuous descent to his rocky demise. I want to ask them whether his death has given them any cause to reflect upon his treatment. If so, what have they learned? Big ideas or tiny changes in practice? What change might they like to bring about so that others might not only avoid his fate, but actually entertain a productive lifelong recovery?

My suspicion is that very few, if any, have reflected much on William and his treatment. Given a lack of time or effort devoted to reflection, I suspect precious little, if anything, has been learned. I am talking about good, well-intentioned people who have dedicated their lives to important work. But is it work so trapped in orthodoxy of practice, work so mired in bureaucracy, that it leaves little time for introspection. How much are those who treat substance use disorder just like those they hope to cure, repeating the same behavior over and over. We ask addicts to look at what they do. We need to ask treatment providers to take a harder look at what they do. Or how about, just a look.

Recovery is like a pinball machine. Up at the top somewhere, protected by bumpers and barriers is a target, prolonged recovery, hit sometimes by good luck, sometimes by good management. Your ball may land in a hole temporarily and then get spit back into play again. That's Emergency Rooms or the court system. Points off for the court system. You might get lucky and hit a treatment gizmo that puts two balls in play--one for substance use and one for mental health issues. Your ball may just get swallowed up for a while before reappearing somewhere by surprise. That's insurance coverage. Or relapse. Points off. The ball may disappear down a hole until it pops up in the starting mechanism. You pull back, let go and start over. Inpatient or outpatient. Or relapse. Points deducted. Up toward the top are some flippers to keep you in play. Methadone. Suboxone. Side bumpers bounce you repeatedly into the center of the game. 12 Steps. DO NOT TILT! The lights flash, the bells go off and you do your best to tune out the frenzy in a game slanted downhill. Over time too many balls roll through that last set of flippers and disappear. Rock Bottom. Game Over.

So why don't we tilt the table? Why don't we take the whole game and flip it on its end so that all the balls roll toward WINNER?!

I can hear someone calling me a bitter, unrepentant enabler right about now. Unwittingly, or even knowingly, maintaining the status quo. I'm tilting the table. Family members are hardly the only enablers, however quickly blame may come our way. When physicians, medical schools, therapists, Twelve Step programs, insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, inpatient and outpatient treatment providers, politicians, judges, drug courts, police, schools and colleges take a good hard look at themselves and ask how they enable addiction, how their actions and ignorance perpetuate it, then we'll have taken a step toward a solution. We can't expect answers and solutions when we resist even asking the questions necessary to solve the problem. IM FLIPPING THE GAME! Who's joining me?